Since 1977,

Walter De Maria’s

The Lightning Field, four hundred stainless-steel poles arranged in a one mile by one kilometer grid in a remote section of New Mexico, has served as the mysteriously elusive

Moby-Dick of modern American art. De Maria limits access to the site itself, requiring visitors to stay overnight and forgo all means of communication with the outside world during their time there. De Maria also fiercely fights against the proliferation of images of

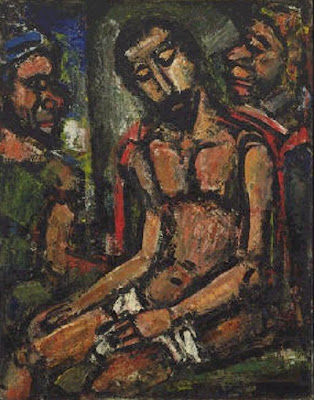

The Lightning Field and has refused to offer interpretations of his work. Into that void steps Kenneth Baker, whose book, titled simply

The Lightning Field (above), breaks the silence surrounding De Maria installation but also reinforces De Maria’s idea that words and interpretations always fall short of reproducing the physical experiencing of the work itself. Words fail over and over for Baker, who is still forced to use them despite realizing their ineffectuality.

The Lightning Field “silences the incessant prattle of consciousness,” Baker writes, but he rises from that silence to speak of the paradoxical power of De Maria’s work to inspire inner and outer explorations in those who open themselves up completely to the experience. Visiting and revisiting

The Lightning Field over a span of three decades, Baker guides us through the grid while emphasizing the need for each of us to serve as our own guide.

Baker was first invited to write on

The Lightning Field in 1977, but De Maria rejected that essay as “too descriptive” and it remained unpublished until now. Baker’s initial reactions, indeed too descriptive for De Maria’s taste, help orient us inside the field while disorienting us enough to think we are truly “there.” “The constant message of TV and of publicity generally is that vicarious experience is real experience,” Baker writes. “But reading this essay is not having an experience of

The Lightning Field, nor is writing it.” Baker beautifully conveys the inexplicable indifference of

The Lightning Field to interpretation. “

The Lightning Field’s spectacle is so detailed and so disinterested in its existence as ‘art’ that I know it will outstrip my ability to describe it,” Baker admits candidly, throwing in the towel in a spirit more of triumph than defeat. As Lynne Cooke writes in her preface, “Too often everything the theorist does succeeds only in becoming, for the novice, part of the educational package into which the object is subsumed.” Baker as critic admits the deadening effect of criticism, allowing the work and his sensory appreciation to live again.

The second essay by Baker collects impressions gathered from visits to

The Lightning Field from 1994 through 2007. Like

T.J. Clark in

The Sight of Death, Clark’s compendium of repeated exposure to two paintings by

Poussin (which I reviewed

here), Baker allows us access to the mind of a deep thinker of art engaging imaginatively a work of art over a period of time, permitting us to witness the evolution of an idea. Unlike Clark, however, Baker refuses to take an authoritarian stance. Clark imaginatively enters Poussin’s paintings, but Baker stands outside

The Lightning Field imaginatively, knowing that “entering” is always an self-deluding illusion. This difference comes across most strikingly in both authors’ approach to the events of

9/11 in relation to the art before them. Clark never overtly claims healing powers for Poussin, but it remains a subtext of the entire book. Baker comes right out and denies art and, specifically,

The Lightning Field status as restorative sites. After 9/11, “many people conversant with the arts turn[ed] to them for consolation,” Baker writes, “

The Lightning Field offers none. This confirms its importance.” As much as we reach out to

The Lightning Field (or any art) for meaning, it will never reach back.

Baker excels in describing this alien and alienating nature of

The Lightning Field. “

The Lightning Field activates one’s submerged sense of the philosophical dislocations the past millennium has effected,” Baker muses. “After

Copernicus,

Darwin,

Marx,

Nietzsche,

Freud, and

Einstein—and some might wish to add

Heidegger,

Foucault, and

Derrida—humanity can no longer locate itself at the center of anything.” Baker shamelessly drops names as shorthand for complex philosophical ideas like a trail of breadcrumbs as he ventures deeper and deeper into the dark forest of the implications of modernity’s solipsism, which he feels “may be the defining sensation of subjectivity in our time.” Baker forges a difficult path to follow, but he’s well worth keeping up with, sprinkling references to comedian

Steven Wright and novelist

William S. Burroughs, among others, to keep things interesting. “The mind of anyone who spends enough time alone at

The Lightning Field may drift to similar extremes,” Baker warns, “all the way to wondering how we ever made a world of what we experience.” Baker’s meandering, like that of a digital age

Thoreau, brings us to the very origin of knowledge, a call for all sleepers to awake and question what and how we know.

“[B]y its very openness—indeed, vulnerability—to interpretation, the work raises the ultimate critical quandary: What can be shared?” Baker asks in the end. The solution he offers is to embrace the ambiguity. “Only when we claim ambiguity as our element, and let ourselves be openly delighted, fascinated, or beleaguered by it,” he believes, “can we accept our position: in the middle of nowhere, in the cosmological and philosophical senses.” Thus, Baker puts a positive spin on a modern version of

Keats’ "

Negative Capability," free of all

Romantic baggage. Like

The Lightning Field itself, Kenneth Baker’s

The Lightning Field is a mind-altering experience, opening up a cosmos of possibility that is both invigorating and terrifying simultaneously. For all his talk of disorientation and decentering, Baker in

The Lightning Field places you firmly at the center of the big questions of art and interpretation.

[Many thanks to Yale University Press for providing me with a review copy of Kenneth Baker’s The Lightning Field.][

NOTE: In the spirit of De Maria and this book, which contains only one photo of

The Lightning Field, I’ve resisted the temptation to include images of the work with my review. You can find them on the web, if so inclined. If you want to follow in Baker’s footsteps and see the real thing, however, you can find the details

here.]

+1845.jpg)

.jpg)

+1665.jpg)