Working as a teenager as apprentice to a glass painter and restorer, Georges Rouault came face to face daily with beautiful stained glass windows showing scenes of the life of Christ. Born May 27, 1871 to a poor, pious Parisian family, Rouault’s faith was always strong, but it was his friendship with the philosopher Jacques Maritain that drove Rouault to commit himself to painting primarily religious subjects. Rouault’s The Flagellation (above, from 1915) shows the lingering influence of stained glass window design in the cloisonnist dark lines separating the fields of color. Christ stands at the pillory in the center of the work to take the blows of the soldiers. World War I raged as Rouault painted this scene of suffering, which may allude to Europe’s self-flagellation in the name of nationalism. It is interesting that Rouault’s works concentrate almost exclusively on the passion and death of Christ, with no images that I know of depicting the triumph of the Resurrection. Rouault identified with agony more than ecstacy, saying once, “The conscience of an artist worthy of the name is like an incurable disease which causes him endless torment but occasionally fills him with silent joy.” Perhaps Rouault allowed himself a moment of “silent joy” upon completing The Flagellation, but the emphasis was definitely on the silence.

In 1920, Rouault painted The Crucifixion (above) in the same stained-glass style with the same contorted limbs. The Fauves claim Rouault as one of their own for his bold use of color. The Expressionists count him among their ranks for Rouault’s tortured rendition of the human body, usually Christ’s. Certainly Emil Nolde’s 1912 Prophet equals the religious fervor and Expressionist angst of Rouault’s religious works. I find it fascinating that Rouault paints Jesus in The Crucifixion without a beard, whereas other works show the familiar bearded face. Michelangelo chose to paint the Savior of The Last Judgment as a beardless youth to allude to the Greek ideal, casting Christ as a new Apollo bringing light into the world. I’m not sure that Rouault shared Michelangelo’s same faith in humanism, especially in 1920, when the aftershocks of the Great War continued to be felt throughout Europe. Maybe Rouault paints Jesus here as the beardless youth to stand for the whole generation of beardless European youth that met their end in the trenches and fields of wartime folly.

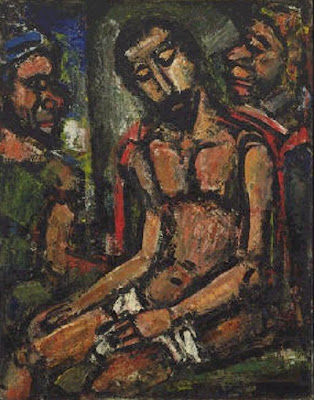

Before Rouault turned his attention to Christ-centered paintings, he painted series of works showing clowns, kings, and prostitutes as a way of commenting on the sad state of modern society. In Christ Mocked by Soldiers (above, from 1932) Rouault shows Jesus at the moment he is forced to play the clown king for the amusement of the soldiers, who crown him with thorns and place a reed “scepter” in his hands. In Christ Mocked by Soldiers, Rouault mocks the world itself, which he sees as prostituting itself for material things at the expense of its soul. “The richness of the world, all artificial pleasures,” Rouault lamented, “have the taste of sickness and give off a smell of death in the face of certain spiritual possessions.” By 1932, Rouault may have recognized, as did many others, the degenerating situation in the world that would eventually lead up to World War II. Rouault returns to the image of the bearded Christ here to emphasize the weariness of age rather than the innocence of youth of The Crucifixion. In his sixties himself, Rouault grew weary of the world and its self-destructive ways. Shortly before his death in 1958, Rouault destroyed three hundred of his own paintings, which would be worth a fortune today, as if to place them on his own funeral pyre and out of the reach of the materialists who valued them in currency instead of, as he did, in Christianity.