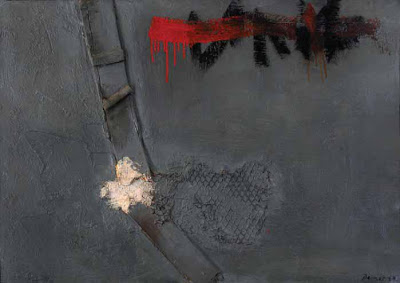

Guillermo Núñez. Saber del dolor, 1967. Oil on canvas. 48 x 65 in. 123 x 158 cm.

Guillermo Núñez. Saber del dolor, 1967. Oil on canvas. 48 x 65 in. 123 x 158 cm.For a country so full of flavor and life, Chile has known more than its share of sorrow and pain. Even before the overthrow of Salvador Allende in 1973, followed by decades of Augusto Pinochet’s reign of terror, Chile’s political landscape in the 1960s served as a battlefield. The artists of 1960s Chile sought to capture the feelings of their nation in a new style of modern art. As part of the Chile in Philly! celebration running through the end of November, selected works from the modern art collection of the Chilean Embassy demonstrate not only the talents of these modern Chilean artists, but also the vision of the Chilean government to collect such important works. Ambassador Radomiro Tomic began collecting modern Chilean art such as Guillermo Núñez’s Saber del dolor (above, from 1967) as Chile found itself “at the threshold of a polarized political confrontation that, like in almost every other Latin American country, ended in a long, dark period of dictatorship,” writes Mariano Fernández Amunátegui, current Ambassador of Chile to the United States, in the Foreword to the exhibition catalogue. Núñez, whose work translates to English as “Knowing the Pain,” studied in Europe before returning to his native Chile in 1968. In 1975, the Pinochet government forced Núñez into exile. Returning to Chile in 1987, Núñez knew firsthand the pain of Chile’s birth as a modern democracy and, like all the other artists featured in this exhibition, painted that pain in his own unique fashion. Núñez’s chopped limbs and garish red background illustrate the human cost of the birthing of Chile’s modern democracy.

As opposed to the macabre imagery of Núñez, Federico Assler paints in a more organic, unifying spirit, such as in De la mano (above, from 1963), which translates to English as “Hand in Hand.” The figure on the left glowing with a hopeful energy links hands with a darker, crimson figure on the right, perhaps transferring that power of hope to those in need. I’m tempted to see the influence of the Italian Futurists in Assler’s abstraction of spiritual electricity conducted through a simple gesture of touch. Assler taught sculpture as well as painting in Chile and influenced the course of cultural education in Chile during the 1960s. Assler’s many public murals spread across Chile bring art and culture to Chileans of all walks of life, democratizing the culture despite the best efforts of those who would keep such art and the hope it represents hidden.

José Balmes, perhaps the most important figure in modern Chilean art, is represented by several works in the exhibition, including Realidad Numero 14 (above, from 1963). In this work, which translates in English as “Reality Number 14,” Balmes clearly tries to translate the reality of Chilean life into art, layering plaster and tablex and covering it with oil paint into a three-dimensional work that confronts the viewer as it leaps from the wall. Balmes came to Chile in 1939 as a young refuge of the Spanish Civil War. After gaining Chilean citizenship, he married fellow artist Gracia Barrios, with whom he founded the Symbolism Group in the 1960s. A militant communist, Balmes fond himself exiled to Paris in 1973 until the late 1980s. Looking at Balmes work, you feel the weight of his life experiences piled up until they almost begin to weigh down your own heart.

Gracia Barrios’s works mirror those of her husband in some ways thanks to their shared use of oil on plaster and tablex. Figuracion (above, from 1963) presents a faceless torso with the contours of the body etched into a thick black slab. Whereas Balmes’ work reaches out, Barrios Figuracion cuts in. Images of the work don’t do justice to the incisions in the dark surface. The facelessness of these torsos mirrors the facelessness of the Chilean masses subjected to the relentless shifts in the political winds as opposing forces vied for control. Although it predates the era of Pinochet’s program of “disappearing” people who opposed his will, Barrios’ Figuracion can easily stand in for those who vanished for their beliefs. In many respects, Barrios’ work reminds me of the dark, sculptural paintings of Anselm Kiefer, who tried to define the horror of Hitler’s Germany for the post-war generation. Barrios, however, defined that horror for her generation, as they actually experienced it.

Fortunately, as Ambassador Mariano Fernández Amunátegui writes in his Foreword, the “long night” that “lasted until the end of the 1980s.. finally gave way to the interesting democratic chapter in which Chile and its neighboring countries find themselves today.” The Chile in Philly! celebration, which includes a celebration of Chile’s food, wine, and cinema, presents the resiliency and vibrancy of Chilean culture. This selection of Chilean art from the tumultuous 1960s reminds us of the distance that Chile has come over the decades as a country and people and makes the joys of today seem all the sweeter. Take a moment to look back on this interesting chapter in Chilean art history as a lens through which to see the Chile of today comes into sharp, brilliant focus.

[Many thanks to Chile in Philly! for inviting me to the opening reception of this exhibition and for the images above. The exhibition continues through November 25, 2008 at the American Institute of Architects in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.]