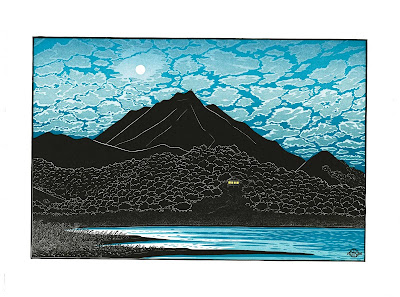

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais From Mill Valley Marshes, 1980 (9 x 12)

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais From Mill Valley Marshes, 1980 (9 x 12) Part of the fascination of Japanese prints is that you envy the Japanese way of living with nature and wish you could somehow import that

Zen into your own life and national culture. Artist

Tom Killion and poet

Gary Snyder’s

Tamalpais Walking: Poetry, History, and Prints from

Heyday Books offers a Japanese import that we can unashamedly use to transport our souls out of the drudgery of American capitalism run amok. Marrying Killion’s Japanese-inspired woodblock cuts (above and below) with Snyder’s Zen-infused verse,

Tamalpais Walking guides us to the foot of

Mount Tamalpais overlooking the teeming Bay City area and makes us feel that we’re actually there, ascending the peak with them. “We who bestow names, who imagine the world from within our human selves,” Killion writes, “what meaning shall we give this beautiful place?” The simplicity of Killion’s images and Snyder’s words opens doors through which we can venture and give our own personal meaning to this place, which resides as much on the Pacific Coast as in the imagination of anyone who reads this book.

Tom Killion, Bolinas Ridge to Duxbury Point, 2004 (14 x 18.5)

Tom Killion, Bolinas Ridge to Duxbury Point, 2004 (14 x 18.5)In 1965, Snyder, along with fellow poets

Allen Ginsberg and

Philip Whalen, founded a circumambulation route around Mount Tamalpais that could be completed in a single day. Snyder had roamed about the mountain since 1948 and wove many of his experiences there into his poetry. In his poem “Hills of Home,” Snyder writes:

to see your own tracks climbing

up the trail that you go down.

the ocean’s edge is high

it seems to rise and hang there

halfway up the sky.

Snyder’s essay in

Tamalpais Walking, titled “Underfoot Earth Turns,” tenderly caresses the land with verbal imagery. Walking among the “strict and thoughtful old trees,” Snyder has come to see Tamalpais as “no longer just a playground or a gateway, but a temple and a teacher, a helper and a friend.” In the end, Snyder asks, “Did we make up that great space, or did it make us up?” Snyder’s soulful appreciation of Mount Tamalpais mirrors that of many great visual artists who find infinity in a single spot, such as

Cezanne and Mount Sainte-Victorie or

Andrew Wyeth and Chadds Ford. I couldn’t help but think of

Thoreau at Walden Pond when reading of Snyder’s obsession with the mountain, especially in the way that both Thoreau and Snyder strive to wake the sleepers around them to the beauty without and within. “If you look, you’ll find a way,” Snyder writes of Tamalpais and, by extension, life.” “A path, a trail, an old road… it’s about discovering mobility, independence, choice, and places to hang out in the underbrush. It’s about getting there on your own two legs.” Snyder declares independence from the American rat race and encourages us to slow down, look around, and live, too.

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais From Above Green Gulch (Coyote Ridge), 2002 (13 x 19)

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais From Above Green Gulch (Coyote Ridge), 2002 (13 x 19)

Just as Snyder presents Tamalpais as a poetic microcosm of what America can be, Killion presents Tamalpais as a microcosm of American history, both good and bad. Tamalpais, the “sleeping lady” of the Bay Area, took it’s name from the local Miwok tribes. When Europeans settled the area and drove the Native Americans out, they kept the name of Tamalpais. The German immigrants who arrived in the 1880s and became the largest immigrant group in the area at the time transplanted their European hiking culture to Tamalpais and searched every inch of their new prize. Some of the earliest conservationists sought to save Tamalpais’ pristine beauty. “An American Wordsworth will one day come to sing these noble trees,” conservationist William Kent predicted in 1908. Killion traces the long line of poets leading up from the mid-19th century to Kenneth Rexroth in the 1930s to Snyder and the Beats of the 1950s and 1960s. Painters and photographers, most notably Ansel Adams, also brought their art to Tamalpais. Sadly, in the 1940s, Tamalpais witnessed the persecution of the local German population and the internment of Japanese citizens during World War II. Killion aptly positions Tamalpais as a wise witness to all these glories and tragedies in American history.

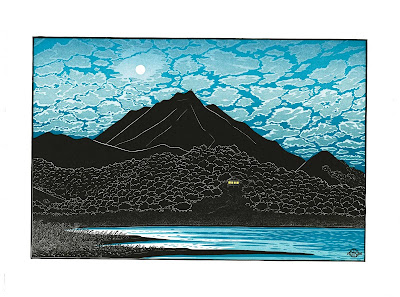

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais, Marin County, 1996 (11.5 x 17)

Tom Killion, Mt. Tamalpais, Marin County, 1996 (11.5 x 17)

Killion takes his rightful place among the great artists who have paid homage to Mount Tamalpais with his insightful and inspired images. Only eight years old when he first hiked Mount Tamalpais in 1961, Killion has studied its sides ever since. The art of Hiroshige and Hokusia, the twin towers of classic Japanese printmaking, inspired the young Killion to follow a similar approach to his personal peak. Killion’s 1975 book 28 Views of Mt. Tamalpais directly referenced Hiroshige’s Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji without slavish devotion but, instead, true homage. The Zen spirit of Hiroshige and Hokusai comes through clearly in works such as Killion’s Mt. Tamalpais, Marin County (above, from 1996). The single light shining through the window of the mountainside home hints at the human presence surrounding Tamalpais while simultaneously conveying how the dark, brooding shape dwarfs mere humanity. Killion’s works always stand in awe of nature. “Just a mountain,” Killion writes ironically of Tamalpais, “but fixed in the imagination of a city.” Killion’s art fixes Tamalpais panoramically into the imagination of anyone who can be open to the love and spirit behind them.

Tom Killion, The City From Mt. Tamalpais, 1979 (5 x 7)

Tom Killion, The City From Mt. Tamalpais, 1979 (5 x 7)

Killion and Snyder’s art forms pair together like the perfect wine and food, composing a nourishing meal for the shrinking soul. “May we all find the Bay Mountain that gives us a crystal moment of being and a breath of the sky, and only asks us to hold the whole world dear,” Snyder prays as a closing benediction to readers of Tamalpais Walking. As much as Killion and Snyder and so many others hold Mount Tamalpais dear, the real message of Tamalpais Walking is for us to “hold the whole world dear” and find our own mountain to stand upon and see the world and ourselves fully, perhaps for the first time.

[Many thanks to Heyday Books for providing me with a review copy of Tom Killion and Gary Snyder’s Tamalpais Walking: Poetry, History, and Prints and for the images from the book.]